| EAGLE CREEK WHOLESALE GROWERS |

| Founded: In 1999 by Jill Cain. Location: Mantua, Ohio. Crops: Annuals, perennials, poinsettias, chrysanthemums, prefinished ferns and Easter crops, Jackson & Perkins roses. Production space: 3½ acres of Prins glass greenhouses, 1½ acres of DeCloet ground-to-ground polyethylene-covered houses and an acre of outdoor production. Market: 30-40 percent of sales go though Eagle Creek Garden Center, 30-40 percent to independent garden centers, 20-30 percent to small corporate chains including grocery stores and independent farm markets. Employees: 15 full-time and 20 seasonal. Sustainability highlights: a 300-horsepower, 5-million Btu Hurst biomass boiler; a 50 kilowatt Entegrity Wind Systems wind turbine; recycling all plastics from the greenhouse operation and from Eagle Creek Garden Center; two 15,000 gallon collection tanks for recycling irrigation water for ebb-and-flow flood floors; three lakes to collect rain runoff; 100 percent of workforce from surrounding area. |

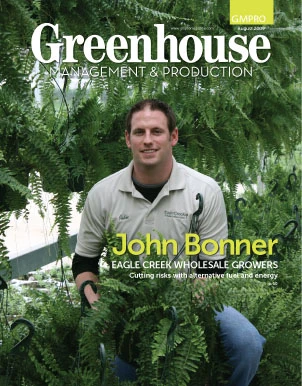

John Bonner, general manager of Eagle Creek Wholesale Growers in Mantua, Ohio, is looking to remove risk from his business. One of the biggest risks he has removed is the fluctuating cost of fuel to heat the company’s 5 acres of greenhouses.

“We made the decision four years ago to eliminate the risk associated with the fluctuating cost of natural gas,” Bonner said. “We were paying $15 per million cubic feet. It was a big stress on us financially. We wanted to free ourselves from those fluctuating costs.”

Eagle Creek chose to install a 300-horsepower, 5-million Btu Hurst biomass boiler that burns a fuel consisting of dried horse manure, wood chips and sawdust. Bonner said the biggest issue for a grower looking to install a biomass boiler is what fuel source is available.

“That may not be the first question that you ask yourself, but it needs to be the last question you answer,” he said. “The fuel source is everything. How long is it going to be here? What does it cost today and what will it cost in the future?”

Eagle Creek collects horse manure from area farms, which is mixed with sawdust and woodchips the grower delivers to the farmers to be used as bedding in the stalls. The sawdust and wood chips are collected from local businesses, including Amish sawmills and a cabinetmaker. Bonner said the economic downturn’s impact on the local construction industry has had an impact on the amount of wood that is available.

“Our fuel price has gone up relative to gas,” he said. “In the short term the construction industry is down so the wood supply is down,” he said. “We made the decision based on the fact that over the next 30 years the price of gas is going to fluctuate. But in five to six years when we pay the boiler off, we won’t have any costs for heat, other than those for trucking in the wood and manure and keeping the boiler operating. We’re going to try to get the fuel back to our facility at a net cost of zero.”

Lower electrical costs

Just as Eagle Creek has taken the risk out of its heating fuel source, it is taking the steps necessary to reduce its dependence on the local electric utility. This spring the company installed a 50-kilowatt wind turbine from Entegrity Wind Systems. Eagle Creek poured the foundation for the turbine and worked with a local installer, Genesis Energy Systems, to set up the equipment. Eagle Creek expects to reduce its annual electrical consumption by 30-40 percent. Installation of a second turbine is planned for later this year.

“Based on local wind data reports, with the turbine that we have installed, we should be able to generate 80,000-100,000 kilowatt hours,” Bonner said. “Our annual usage is about 300,000 kilowatt hours. One turbine should handle one-third of our electrical usage.”

Bonner said that the company’s peak period for usage mirrors its wind resource.

“Our electrical needs spike in the winter when we are pushing our production,” he said. “We have all our automated equipment running along with having the lights on all day. During the summer when we are not as busy and the electrical demand is less our wind resource is also lower.

“We have 1,000 acres of land here, so this might be a great spot to have several wind turbines,” he said. “We could put up enough turbines to run our entire farm operation. We have corn dryers and other equipment that use a considerable amount of electricity. We’re going to wait and see just how much electricity this one turbine generates.”

Eagle Creek worked with the USDA and the Ohio Department of Development to obtain development grants to pay for the turbine.

“We were only 25 percent cash out of pocket for the total cost of $250,000 for the turbine,” Bonner said. “A USDA grant paid 50 percent of the cost and a federal grant paid for 25 percent. We figure to pay pack our cost in four to five years. We are submitting a grant proposal for a second turbine and should know by November.”

The turbine manufacturer helped Bonner with the grant-writing process. Having gone through the process, Bonner expects his company will submit additional proposals in the future.

“There are subsidies available now for lighting,” he said. “We have metal halide lamps in our warehouse. If we replace those lights with more efficient high bay fluorescent fixtures equipped with motion sensors, we can receive a tax credit of 60 cents per square foot. Couple that with the two wind turbines and we have cut our electrical costs down considerably. Lowering consumption to help our bottom line and looking into government subsidies, these are the kind of things we are looking for now.”

Picking pots that work

Bonner, whose father and mother started Dillen Products, grew up with plastic pots and still buys pots from the container manufacturer, which is now owned by Myers Industries. Eagle Creek has trialed several different biopots, but has not been satisfied with the results.

Bonner has been working for about a year with U.S. Liquids, a local plastic recycling company, to recycle all of Eagle Creek’s plastic containers, plastic baling wrap and other injected molded materials.

“We collect the plastic here and at our retail garden center and then sort it into three different bins (polypropylene, polyethylene and polystyrene),” Bonner said. “When we go out to Dillen to pick up our pots, we drop off the used plastic and make a little money recycling it. We’re still realizing a cost savings from plastic pots. Dillen is right up the street from us and its employing local people. These plastic containers don’t have to be shipped a long distance like some of the eco-containers. The plastic pots also work with our automated equipment and they hold up in production in the greenhouse.”

Although Bonner has yet to find the perfect biopot, he has been happy with the results of the ITML coir pots he has trialed. The coir pots work with the company’s flat filler.

“We’re producing about 50,000-60,000 vegetables and herbs in the coir pots,” Bonner said. “In our trials the plants developed nice, healthy roots in the coir pots, which provide some air pruning. Each of the pots comes with our Earth’s Choice tag.”

Alternative crops

In 2010, Eagle Creek is planning to offer an organic line of vegetables. Bonner has spoken with Mark Elzinga at Elzinga & Hoeksema Greenhouses in Portage, Mich., who is currently selling organic vegetables, about the logistics of producing an organic crop.

“We plan to offer an organic line at our retail location,” Bonner said. “We’d like to build a ¼-acre production area for the organic line. We would also need separate receiving and shipping docks. A big challenge for Mark was trying to locate organic starter material. I’ve talked to Mark about if you’re not organic are you sustainable. I think you can have sustainable business practices without being organic. But I think there is an increasing pull by the public and retailers to go organic.”

Bonner said one of his big challenges is finding new products he can produce from October through January. He has cut back on the number of poinsettias he is growing because of the competition and prices in the Cleveland area. With the installation of the boiler and wind turbine, Bonner is now able to consider crops that may not have been economically feasible in the past because of the need for higher light levels and warmer production temperatures. Eagle Creek is also expanding its production of prefinished 10- and 12-inch ferns and prefinished Easter crops including lilies and hydrangeas.

“We’re doing more ferns because we now have the heat to grow them,” Bonner said. “I don’t know what these ferns are selling for coming out of Florida, but I bet we can produce them for a similar cost depending on what it costs to truck them up North. It’s so cheap for us to heat now.”

| ENSURING AN ADEQUATE FUEL SOURCE |

|

With the installation of a 5-million Btu Hurst biomass boiler, Eagle Creek Wholesale Growers needed to be sure that it had an adequate fuel source to burn. General manager John Bonner is working with local horse farms to collect manure that is stockpiled and dried at Eagle Creek. |

For more: Eagle Creek Wholesale Growers, (330) 569-7933; www.eaglecreekgrowers.com.

Explore the August 2009 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Hurricane Helene: Florida agricultural production losses top $40M, UF economists estimate

- No shelter!

- Sensaphone releases weatherproof enclosures for WSG30 remote monitoring system, wireless sensors

- Profile Growing Solutions hires regional sales manager

- Cultural controls

- University of Maryland graduate student receives 2024 Carville M. Akehurst Memorial Scholarship

- Applications open for Horticultural Research Institute Leadership Academy Class of 2026

- Meeting the challenge of pest management