Photos © Chip Morton, Gabe Wasylko and TIME magazine

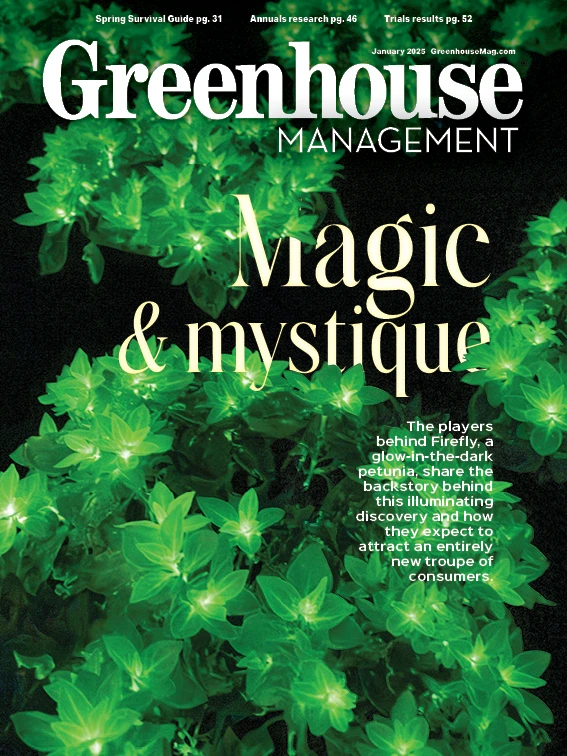

An unconventional team of horticulture pros and bioengineers have sparked a glimmering curiosity among consumers with the release of the Firefly petunia, touted as the world’s first commercially available glow-in-the-dark plant. During the day, Firefly looks like a basic white petunia. But in the dark, Firefly exudes a luminescence from the roots up to the flowers. Every part of this bioengineered plant is capable of glowing.

When Susie Raker, vice president of Raker-Roberta’s Young Plants, heard about Firefly for the first time a little more than a year ago, she was hooked. But she hadn’t even seen the plant in person yet when she agreed to be part of the team tasked with getting the glowing achievement to market.

“I immediately said, ‘I’m in. Whatever you need. Let’s make this happen,’” Raker recalls. “I would have been crazy not to get involved. And once I saw the plant, I fell in love.”

The science behind Firefly

The origin story of the Firefly petunia begins with the glimmer of fascination Keith Wood felt as a young teenager studying basic biochemistry. As he grew and learned more, he dreamed of exploring molecular engineering. Serendipitously, a genetic engineering revolution was underway that eventually would light a path to successful discoveries for Wood across several decades.

Wood, who has a master’s degree and Ph.D. in chemistry, has been working with bioluminescent plants since the 1980s. He was part of a team at the University of California San Diego who made the first bioluminescent plant through genetic engineering. They cloned a gene that encodes a group of enzymes that makes fireflies glow.

“The gene ended up being really useful for studying how other genes work,” Wood explains. “In this work, we started to use this bioluminescence gene to see genetic regulation. When we put that gene in a plant, we made the first bioluminescent plant.”

Prior to this discovery, genetic engineering didn’t mean anything to the general public, he says. “They really couldn’t understand it. The press was writing about it, but they couldn’t really show it,” he adds. “But when we made this glowing plant, it became an icon of this entire genetic engineering field. It was the first time you could really see the evidence of genetic engineering.”

The plant and the scientists made all the evening news programs, TIME magazine, Newsweek — it was a big deal. They even got a mention in Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show monologue.

After the discovery, several groups tried to make more bioluminescent plants, thinking it would be a novel item to sell.

“The concept was fine, but I knew that technically what they were trying to do wouldn’t work. And there were many notable failures,” Wood recalls.

Wood left university research and brought his bioluminescence knowledge to a biotech company where he worked for decades. In another opportune instance in Wood’s career, a colleague discovered a new type of bioluminescence in mushrooms.

“Once we understood the molecular foundations of this new system, we knew this would solve the problem people had been trying to overcome for decades. I resigned from my position as head of research at a large biotech company and started Light Bio,” he says. “For years, there’d been a great deal of popular interest in bioluminescent plants because people found something magical about them. With the new discovery, our purpose was to bring this idea, this aspiration, to reality.”

Wood and his business partner set out to use science and advanced technology to “bring enjoyment to people’s lives,” he explains. “And that’s really a departure from the typical missions of biotechnology.”

Despite the mushroom discovery, it still took nearly a decade for Firefly to go from initial idea to commercial product.

But why a petunia? For several reasons, Wood says. When scientists study the molecular biology of plants, they typically experiment with two plants: Arabidopsis, a “little, somewhat ugly and weedy plant” and tobacco. It was obvious they weren’t going to sell a bioluminescent tobacco plant, but they could sell a close relative: petunia.

“They’re in the Solanaceae family, so we could take what we’d already developed in tobacco as an experimental model and move that into a petunia, a popular bedding plant,” he says.

From the lab to the greenhouse

After years of work, Wood finally had a plant to take to market. Knowing the petunia was a huge part of what he describes as a finely tuned industry, Wood acknowledged he needed help from the horticulture world.

“We weren’t going to build our own greenhouses. We weren’t going to optimize production. We weren’t going to create new distributions,” Wood says. “That’s all been established. What we needed to do was insert ourselves into that system. Our plan was to be the experts in how to create this plant and partner with people who are experts in how to manufacture and distribute this plant. The challenge for us was to find people who are creative enough, who are entrepreneurial enough to take a chance on us and make this thing happen. And then I met Susie.”

Wood remembers that Raker may have thought him a bit naïve and but was willing to take a chance on a crazy idea from a biotech guy. “And as she got involved, she realized this is really something special. And I realized that she had quite a talent and a proven track record of success,” he says.

Once Light Bio received approval in the fall of 2023 from the USDA to sell Firefly, Wood and Raker scrambled to get enough plants in production to sell direct to consumers on the Light Bio website.

“Our initial goal was to sell 30,000 units, and we ended up selling 120,000,” Raker says. “And people were paying $60 or $70 once shipping was included for a 4-inch pot.”

Raker attributes much of that initial success to production manager Casey Stanton and quality manager Jarvis Green, who worked to tweak production processes and learned the best management practices for growing Firefly. While it’s a petunia and has some of the same needs as a standard petunia, “she’s a little finicky and requires some special care, and that's because of the genetic work that’s gone into this plant,” Raker notes.

“She’s a heavy feeder, a light rooter, and may get some mottling on the leaf during certain stages of production, but she grows through it. She always comes back clean. There’s no virus. She’s day-length neutral, and she flowers her head off.”

For 2025, Firefly sales to the trade will be managed by Rooted in Solutions, a company Raker founded that acts as a product development firm handling supply chain management, marketing and breeding of the new plant. Stanton and Jim Devereux, CEO and co-founder of Green Fuse Botanicals, are part-owners of Rooted in Solutions. Devereux is managing tissue culture production of Firefly.

A grower network will distribute finished plants to brick-and-mortar independent garden centers. No big box retailers will be able to sell Firefly in 2025. And Ball Horticultural will offer an exclusive pre-intro liner program to the trade through Raker-Roberta’s.

“This product deserves a different approach — more of a boutique approach because it is so unique,” Raker says. “As I’ve rolled this out to the industry, there has been some skepticism because of the price point, and I get that. But this product is exceptional. Firefly is truly magical. It is magic. And I’m not a ‘soft’ or ‘magical’ type person. It’s one of a kind.”

Raker says she’s always been completely honest about some of the extra care needed in production but has realized “this is probably the easiest item I’ve ever sold in my life. You can position this plant to use in containers outside or you can position this as a houseplant, which is a huge paradigm shift for our industry. A glow-in-the-dark petunia as a houseplant.”

The consumer connection

In November 2023, Jennifer Moss, CEO of Moss Greenhouses in Jerome, Idaho, got a call from her uncle.

“He tells me, ‘There’s this guy that wants you to grow glow-in-the-dark petunias.’ And I just kind of laughed and said, ‘That’s not a thing. OK, give him my number, and I’ll run him off.’ That was literally what I said,” Moss recalls.

But she didn’t exactly “run him off.” It turned out Keith Wood wanted to meet in Twin Falls. He didn’t live too far away. The rendezvous was arranged, but what Wood presented wasn’t particularly impressive, Moss recalls. “He shows up with these two scraggly looking, overgrown petunias. My production manager and I just looked at them and thought, ‘That’s it? OK.’”

Wood explained that Light Bio was growing 100,000 Firefly plants and selling them direct to consumer through the company website. Moss was skeptical.

“I asked him who was growing the product, thinking he can’t possibly be selling the plants I’m seeing,” she says. “He tells me a greenhouse in Michigan is growing them, and I push him to tell me who. ‘It’s Susie Raker,’ he tells me, not knowing Susie and I are good friends. I texted her under the table and asked, ‘Is this guy for real?’ and she answered, ‘Sit down and listen.’”

On the advice of her friend, she did listen. Shortly after, Wood brought her a 72-cell tray of good-looking plants. He needed 500 plants for a wedding in June. “I told him we could grow those for him in time,” Moss says.

Moss’ team thought it was a one-and-done deal. And they remained skeptical about the plants’ ability to glow. But Moss was ready to take on this project.

“I told my team, ‘This is really exciting. It is preemptive. And we want to be at the front of this, not the back of this.’ So, we started to plant some stock plants and worked heavily with the Raker team to figure out the cultural information and figure this out,” Moss says.

Next, Moss approached Adam Thompson, the retail manager of Moss Greenhouses, about selling the stock they’d built up. His reaction was one of puzzlement. But he came up with a plan: host an event in the dark. And the Moss Greenhouse Illuminate the Night event was born.

“What started as a small idea got really big really quickly. So, I called my contacts at the Boise news stations, and they quoted me as saying these plants are ‘straight out of Avatar,’ and it took off,” she says. “What I thought was going to be 300 or 400 people, a guy with a guitar and two food trucks turned into 1,000 to 1,200 people, a full band, six food trucks, a full bar, an axe-throwing trailer and even a massage therapist in the parking lot. Once it got dark, we had fire spinners. We basically ended the night with a rave in little Jerome, Idaho.”

Moss recalls how as soon as people showed up, they got in line to see the “straight-out-of-Avatar” plants.

“The first thing they’d do is get in line to go in the greenhouse. We originally didn’t plan to open the greenhouse until dark, and we only wanted 20 people in the greenhouse at a time. We had a security team at the front of the greenhouse, and this line was 150 to 250 people deep for four hours solid,” she says. “We had a three-plant limit, and people were bringing their sister, their daughter, grandma, their aunt, and each one of them is buying three at time. They’re dropping $90 like it’s no problem.”

Moss sold more than $50,000 worth of plants (not just Firefly petunias) after 6 p.m. The event lasted until 11 p.m.

“I joke that this plant broke gardening for us. But it’s not really a joke. The potential for this plant now and in the future is going to be insane,” Moss predicts.

Moss also works with Rooted in Solutions and helps create marketing materials for the trande. And though the plant is rooted in research, the marketing leans more into experience than science.

“The value is the experience, but the science gives more substance, more background to what made that experience possible,” Wood explains. “They’re buying it because they love the experience of this living presence. There’s a kind of spiritual energy they get from these plants, and different people get different things out of it. It gives you this tranquil connection with this living energy.”

Next in line

Wood and his team are working on the next generation of Firefly and other bioluminescent plants.

“We’re improving the genetics, and we’re improving the methods of production. I expect we’ll get brighter plants, more robust plants,” he says. “As we continue to advance, we’ll have a range of cultivars that serve different kinds of needs. It’s a combination of molecular genetics, conventional genetics and experience that all just add up to better products.”

Besides new plants, Light Bio is creating whole new markets and new divisions, Green Fuse’s Jim Devereux says.

“We’re used to having garden plants, vegetables, potted plants, houseplants, cut flowers. Now we’ll have bioluminescent plants. And it’s completely earth-shattering to have them indoors and outdoors. We’re selling a bioluminescent plant to the consumer, whether that’s a gardening consumer or a person who’s never bought a plant or planted anything in their life. Our market just opened up to anyone who’s got a debit card.”

For his part, Wood views Firefly in a spiritual light.

“There are fascinating historical texts about the quest to extract the vital essence from things like plants. So many of the terms we use today come from this belief that within the tangible existence of plants and animals, there’s an internal vital essence,” Woods says. “It is the soul we care about, not the tangible exterior. This luminescence, this living energy is as close to touching the soul of these things as you can get, and I think that’s really exciting.”

Explore the January 2025 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Anthura acquires Bromelia assets from Corn. Bak in Netherlands

- Top 10 stories for National Poinsettia Day

- Langendoen Mechanical hosts open house to showcase new greenhouse build

- Conor Foy joins EHR's national sales team

- Pantone announces its 2026 Color of the Year

- Syngenta granted federal registration for Trefinti nematicide/fungicide in ornamental market

- A legacy of influence

- HILA 2025 video highlights: John Gaydos of Proven Winners