Frank van Kleef, CEO of Royal Pride Holland Frank van Kleef, CEO of Royal Pride Holland |

On a beautiful sunny day in southern California, Casey Houweling happily greeted guests as they arrived at Houweling’s Tomatoes. He shook their hands, exchanged business cards and laughed as they conversed, but most importantly, he welcomed everyone to his family’s operations because it was a special occasion.

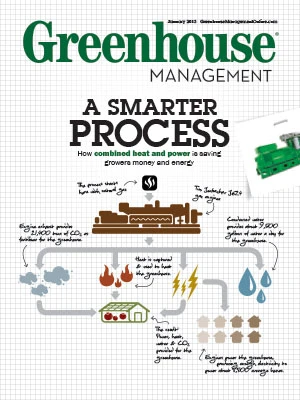

That day was a first — the day the first combined heat and power (CHP) greenhouse project that captures carbon dioxide for use in plant fertilization in America was unveiled. The system Houweling’s installed will save them money and provide nearly 90 percent total thermal efficiency.

“Our costs of production are high in California, and thus we need to make the best use out of everything you do,” says Houweling. “Margins are too tight to be wasteful.”

Buzz certainly filled the air, but surprisingly, this wouldn’t even make news in Europe because it’s already so commonplace there.

“They’ve been using it since the 1990s in Europe,” says Scott Nolen, product line management leader for GE Gas Engines. “We operate around 1,000 engines in the Netherlands alone doing this — that’s just for greenhouses.”

Frank van Kleef is the CEO of Royal Pride Holland in The Netherlands, and his 114-acre business has been using CHP for six years.

“We found out that this is a much more sustainable way of using energy,” van Kleef says. “We have lower energy costs — that is much more sustainable. We need that waste heat and CO2, so all together, we have an energy efficiency of 95 percent now, which a big power plant is not more efficient than 50 percent.”

It’s no secret that the North American market is behind the curve when it comes to the Dutch and other European growers, and this is one other way they’re exceling.

“Greenhouses in Europe just looked at it and said, ‘Wow, this is a way to save a lot of money because I’m buying power from this grid — it’s not cheap. I’m buying gas to heat my place – that’s not cheap. I’m buying CO2 — that’s really expensive. Wait a minute, I can do all this with one thing, and I can save a lot of money,’” Nolen says. “It’s possible in the U.S. that historically, people haven’t considered that because power is cheaper here, gas is cheaper here, CO2 is probably about the same price, but at the end of the day, any way you look at it, it saves a lot of money — even at the lower U.S. prices.”

But it’s not just the Europeans that are more advanced in this area. Nolen explained that this is becoming more commonplace in many developing areas of the world as well.

“I’ve studied a lot about developing countries, but the curse of being a developed country is we have a lot of power in this country and a lot of electricity already installed — but it’s inefficient power,” Nolen says.

He explained the problems with our power sources: about 50 percent of our power is coal power, which tends to be less efficient. We also have nuclear plants, and their fuel costs are low, but there are other issues with those plants. There are also gas plants, and those are a little more efficient.

Top: Scott Nolen with the Houweling family. Bottom: A Jenbacher J624 gas engine. Top: Scott Nolen with the Houweling family. Bottom: A Jenbacher J624 gas engine. |

“We have a lot of power, so people aren’t being encouraged too much to put in new power, even though new power is so much more efficient,” he says. “If you think of a developing country in Africa that is thinking of doing this, the plant they put in now would have this in there, and they would be ahead of the curve, where it’s hard for us because we already have all this power installed. You always think of the United States as being on the cutting edge of everything, but in the case of power production, we’re lagging behind the rest of the world.”

This is one way that growers can make changes to stay more relevant.

“We waste far too much energy in this country,” Houweling says. “If we do not get a better handle on our energy usage and costs, we will become uncompetitive.”

CHP 101

So what exactly is this CHP that’s going to help growers be more competitive? It can be technical and a little complicated to understand, but what it boils down to is fairly simple.

“With this engine, I can generate electricity for my lights, hot water to heat my facility and CO2 to fertilize my facility — just with the engine,” Nolen says. “It’s obviously more complicated to execute all of that but in a nutshell, that’s what you do.”

So how does that work exactly? To start, let’s look at the typical way power is generated now.

“Let’s say you have 182 units of energy that goes into a traditional power plant today,” Nolen says. “So somebody needs electricity and heat — a chocolate factory, an airport, a shopping mall, whatever — so 132 units of energy have to be produced to get the electrical power that you need. Then you have to do another 50 units of that energy to generate the heat that you need. What ends up happening is, of that 182 units of energy that you put in, 92 of it is wasted because the grid is only 34 percent efficient. Eighty-seven of those units are lost to heat at a traditional power plant.”

In total, about half of what is generated is lost because a traditional plant just loses it.

‘Houweling’s Tomatoes is the first greenhouse to use CHP in America. ‘Houweling’s Tomatoes is the first greenhouse to use CHP in America. |

“In combined heat and power, if I have 100 units of energy, I can use 45 for electricity, 45 for heat and only lose 10 percent,” he says. “I save all that energy that would be lost or a very large portion of the energy that would be lost in a traditional plant. If I do combined heat and power, and I want to heat a greenhouse, it saves an incredible amount of energy.”

In addition to saving energy, it helps reduce costs all around.

“When electricity is generated, in most cases, the waste product is heat and CO2, our second and third highest cost,” Houweling says. “It seems a no brainer to utilize this waste.”

The cost to install depends on how much heat you need.

“If you can use all the heat, it really is not that much more expensive than buying the boiler because you have to buy a boiler anyways to heat the building of the structure, so the costs can be very competitive against the boiler,” Nolen says.

The only way it can end up costing you a lot more money is if you don’t need the heat and power. “If you shut down the greenhouse, it’s not very good anymore,” Nolen says. “Unless somebody came along to you and said, for some crazy reason, I’ll give you power for 1 cent per kilowatt hour or gas for $1 per million BTU — it almost becomes free — then yeah, you’ve wasted your money in the installed cost of the equipment, but most people aren’t that lucky. Most companies out there aren’t going to get free power and free natural gas.”

A side benefit is that in a lot of places across the country, it’s cheaper to generate your own electricity using natural gas than it is to buy from the grid, and that’s without using the heat, because natural gas has become so affordable in the United States. Additionally, Nolen says that about one-third of the cost of electricity is a fuel cost to transport it from where it’s generated to where you’re taking it.

“If you can generate it yourself, you save all that cost,” he says. “It’s actually cheaper for people, and they’re doing this with our engines. They’re saying, ‘I don’t know if I need the heat or not, but I can generate the electricity cheaper myself than it is to buy it from the grid right now.’ For a greenhouse operator where they have to use lights most of the year, that makes a heck of a lot of sense. Plus they get all the other benefits.”

The beauty of CHP is that you also don’t have to be a large grower like Houweling’s to see the benefits. Houweling’s uses three of GE’s largest gas engines that are 4.4 megawatts, but GE also builds an engine that is a half a megawatt.

“You can have a small greenhouse next to an office building or a shopping mall, and you can share the power,” Nolen says. “You can sell the electricity to them and use the heat yourself. They’re happy because they’re probably getting power cheaper than they’re getting it from the grid. You’re happy because you’re getting the heat and the CO2. People just have to think a little bit differently than they normally have thought and say, ‘Hey, if I think of this differently than just going out and buying gas, buying heat, buying CO2, it gets interesting really fast.’”

Points to consider

It’s important to note though that selling electricity can be difficult in some places, such as California where Houweling’s is located. He’s going to be able to do it, but it’ll be challenging. In other places, such as the East Coast, Texas, the Northeast and the central part of the country, it’s a little easier to sell to the grid, according to Nolen.

If you’re interested in exploring this kind of technology for your greenhouse, Nolen encourages you to look locally for assistance as well.

“There are a lot of incentives right now in the United States for CHP,” he says. “It’s very possible that they could get some good government incentives, depending on the state they’re in and their power authority.”

Some states, like Massachusetts, are encouraging people to do CHP and will pay for a portion of the installation costs.

“They should look around and say, ‘Not only can I get a lower operating cost, but I can install this equipment, and it doesn’t really cost me that much, so my payback goes from five years to two because the government helped me put it in,’” Nolen says. “That’s a real big benefit for people.”

“They should look around and say, ‘Not only can I get a lower operating cost, but I can install this equipment, and it doesn’t really cost me that much, so my payback goes from five years to two because the government helped me put it in,’” Nolen says. “That’s a real big benefit for people.”

Houweling is excited about how its CHP engines will help the business moving forward, and encourages growers to do their homework before they rush out to start using CHP.

“Be very careful of the regulations and resulting delays and added costs,” he says. “They can be very substantial.”

He says to also look at some of the other added costs CHP can bring to your business that may not cross your mind initially.

“There is more equipment, more maintenance and better-qualified staff that’s needed,” he says. “It also uses a large amount of capital.”

Van Kleef also has tips for growers who are thinking about CHP.

“Look at it with an open mind, and look at all the options,” he says. “If you are able to sell back to the grid and have natural gas available, CHP can help to lower your energy cost. In the meantime, you will have a lot more CO2 available.”

Explore the January 2013 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- A nation of gardeners: A history of the British horticulture industry

- Last Word with Angela Labrum, Bailey Nurseries

- Iowa plant supplier Plantpeddler building retail complex

- This month's Greenhouse Management magazine is about native plants and sustainability

- The HC Companies, Classic Home & Garden merge as Growscape

- Terra Nova releases new echinacea variety, 'Fringe Festival'

- Eason Horticultural Resources will now officially be known as EHR

- BioWorks receives EPA approval for new biological insecticide for thrips, aphids, whiteflies