For Miles Jonard, collaboration is key.

For Miles Jonard, collaboration is key.

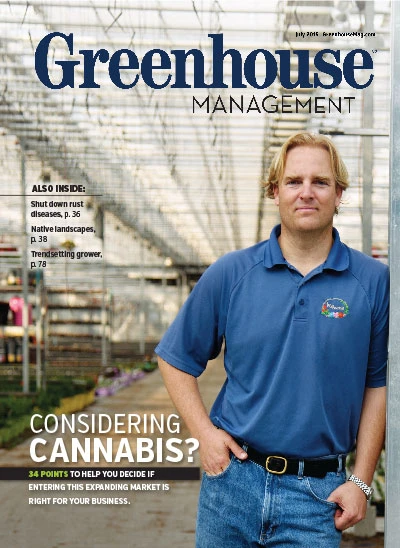

After graduating from Ohio State Univeristy with a Bachelor’s degree in agriculture and a Master’s Degree in horticulture, Jonard trekked from the scarlet-and-grey portion of the Midwest, to the rainy Northwest, becoming the production manager for Solstice, a Seattle-based medical marijuana operation. Now he spends his days overseeing the day-to-day cultivation of cured cannabis.

Jonard’s first experience with plants was in high school. He took a botany and biology class in high school, had an instant affinity for plants and decided to pursue it professionally. But Jonard also wanted out of the laboratory.

“I think at some point I was like, ‘I don’t want to live the rest of my life in a laboratory. I would like to be in the sun,’” he says.

Now, as part of a small but dedicated team, Jonard is overseeing every facet of production.

“Everyone does everything [at Solstice],” he says.

Learning the game

With training in flowers and agriculture, Jonard had to teach himself how to grow a new kind of crop.

“There was definitely a learning curve that was involved with it,” he says. “It’s hard to compare it to another crop because it is so different. It has different growing conditions. It also goes through a curing process like tobacco, so there’s that component, but we grow it inside. I would compare it to a specialty potted crop such as poinsettias, or mums, because a lot of the pruning techniques are similar.”

He says that the goal is to prune the crop to grow the maximum amount of flowers.

Cannabis is a photoperiodic crop, so during flowering, there is a 12-hour light cycle. To even out the load electricity-wise, Jonard says, half of the grow rooms are on a morning schedule, which is12:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., and the other half are on an evening setup, 12:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m.

“So in the morning we come in and do a walkthrough of the morning rooms, the a.m. rooms. I have a team of four, so it’s myself plus four other guys, and I liken the walkthrough to a doctor’s rounds,” he says. “We walk through and we look at every room, and kind of see what kind of work needs to be done in there because it’s such a sensitive crop, and it needs special treatment every day.”

“So in the morning we come in and do a walkthrough of the morning rooms, the a.m. rooms. I have a team of four, so it’s myself plus four other guys, and I liken the walkthrough to a doctor’s rounds,” he says. “We walk through and we look at every room, and kind of see what kind of work needs to be done in there because it’s such a sensitive crop, and it needs special treatment every day.”

Then he assigns tasks for that whatever is needed, including seeding, or watering, or whatever manner of pruning that needs to be done.

“We have scheduled days specifically where sprays happen if they’re needed for that week. Usually the guys get to work, and if I don’t have any administrative stuff to do also, I get to work with some hands-on stuff, or work on more managerial, administrative tasks. It’s sort of like no job is off-limits for anyone. Everyone does every job we have here,” he says.

Jonard will frequently spend another portion of his time working in Solstice’s nursery.

“We produce all of our plants asexually from cloning off other plants. Then generally I focus on whatever sort of daily care the nursery needs,” he says.

Because of the nature of the crop that Jonard is producing, all of his plants must be sold within Washington state lines. And, in addition to the legal restrictions, there is a second half to the production process.

In ornamental flowers, once the plant is grown and harvested, the grower’s work is done. In cannabis, the plant must go through a more elaborate curing process.

“I grow it, then the other half is curing and processing it, then we come out with our harvest unit,” Jonard says.

Changing the game

In time, Jonard would like the cannabis industry to mimic the ornamental horticulture industry. Loads of growing information is considered proprietary and is guarded closely by individual companies. With a lack of significant research being conducted by universities, Jonard feels there is a gap of missing knowledge.

“One of my goals is to have a breeders and growers association that gets together and actually has conventions,” Jonard says of the cannabis industry. “It’s a pretty small market still right now, as far as the people who are doing it, and we’re kind of restricted by state regulations. So it’s not really a national thing that’s happening yet. But I would like to see more communication and sharing of knowledge, growing knowledge and techniques.”

While remaining within the bounds of his non-disclosure agreement, Jonard tries to be as open and honest about his growing methods, his experiments, his successes and failures, as he can be. Part of the reason he’s willing to share cultivation tips and tricks, is his strong belief in the importance of cannabis genetics.

“Genetics are a really big deal with cannabis. If you’re a breeder, or you work with a reputable breeder that comes out with a cultivar, that’s going to be great for you. You’re going to grow that. It doesn’t matter if everybody else is growing the same way that you are. You have that special cultivar,” he says. “That happens in the rest of the horticulture industry. I don’t understand why we don’t have that yet, but we will.”

For his own career development, Jonard wants to be involved with the founding of more cannabis growing organizations and associations. “I would like to see myself growing as more of an advocate [for the industry] not for legality reasons, but as an advocate for growing and communication,” he says.

Why is Jonard so passionate about intra-industry talking and sharing?

“That’s how we get better. It’s one of the most difficult things,” he says. “I can’t go to any large company like Syngenta or Ball Horticultural, and buy some growing guides for the cultivar that I have because it doesn’t exist.”

Predicting the game-change

It seems like the cannabis landscape is changing every day; legally, culturally, economically. The majority of growers appear to be in factory or indoor settings, as opposed to outdoor or greenhouse environments. That’s something Jonard sees changing.

“Outdoor growing is obviously a lot more cost-effective just because we’re not putting so much electrical energy into powering all our lights,” he says.

He also thinks that the culture sharing he wants to see isn’t far off. With time, Jonard believes, breeding companies will gain traction and cannibalize smaller breeders, until there are major brand names. Once those names are established, they’ll be more willing to share best practices with growers who buy their seeds.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

Explore the July 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Trends: Proven Winners 2025 perennial survey shows strong demand

- Online registration opens for the 2025 Farwest Show

- Sustainabloom launches Wholesale Nickel Program to support floriculture sustainability

- Be the source

- pH Helpers

- Society of American Florists accepting entries for 2025 Marketer of the Year Contest

- American Horticultural Society welcomes five new board members

- Color Orchids acquires Floricultura Pacific, becoming largest orchid supplier in U.S.