Tina Smith Tina Smith |

Increasingly, greenhouse growers are taking an interest in the use of biological controls to manage pests. Some growers are using banker plants to sustain natural enemies within their crops to suppress certain pests. Banker plants serve as a rearing system for natural enemies. The plants supply a food source (non-pest species) for a continual supply of natural enemies that disperse into a crop in search of pests. Growers are also looking at using mixed habitat planters in their greenhouses to lure native natural enemies and create habitats for natural enemies that have been released.

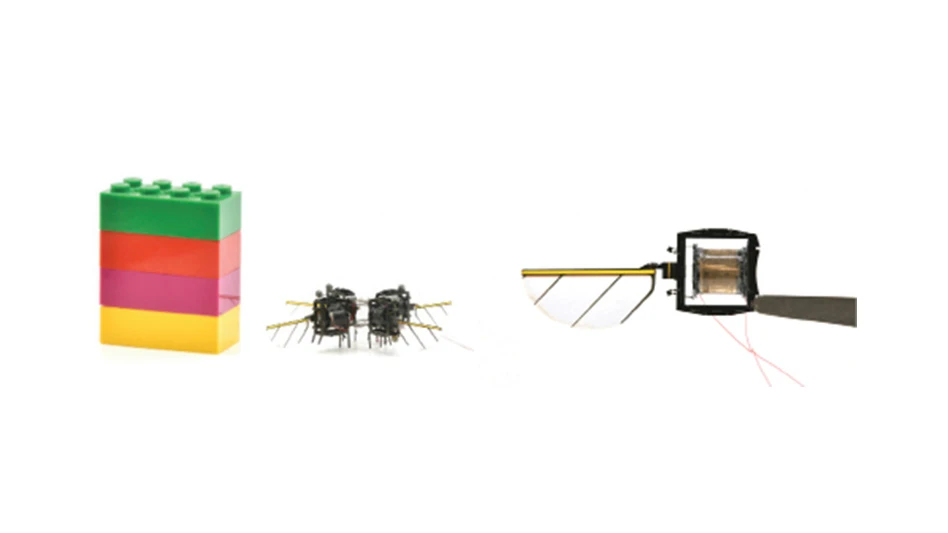

Releasing natural enemies

Research using plant and natural enemy systems on greenhouse crops has focused on releasing natural enemies that have been purchased from a supplier on plants inside greenhouses. Natural enemies require adequate supplies of nectar, pollen and herbivorous insects and mites as food to sustain their populations. The best source is often flowering plants. Flowering plants are particularly important to adult wasps and flies which may use nectar and pollen sources to produce eggs that ultimately parasitize or prey on insect pests. However, a random selection of flowering plants may favor pest populations. It is best to select specific plants for specific known-to-be-present pests.

Carol Glenister of IPM Labs can be seen in a You Tube video discussing natural enemies in a mixed planter. The planter contains barley as an aphid banker plant that supports a parasitic wasp for aphid control, marigolds to support predatory mites for thrips control, lantana and Garten Mister fuchsia to support a parasitic wasp for whitefly control, and Black Pearl ornamental pepper to provide pollen for Orius, a predator for thrips control. Each habitat plant provides a natural enemy targeting a specific pest.

Farmscaping is a term used to describe a whole-farm, ecological approach to pest management. It is the use of hedgerows, insectary plants, cover crops and water reservoirs to attract and support populations of beneficial organisms such as insects, bats and birds of prey.

Greenhouse growers are considering a form of farmscaping that involves the use of a cover crop around the perimeter of their outdoor growing fields to provide a favorable habitat for natural enemies. Like other aspects of pest management, this strategy should be carefully tailored to the individual site and closely monitored and managed.

Farmscaping considerations

There are some problems that can arise with farmscaping. Plants providing the natural enemy habitat, may sometimes also harbor pests. Therefore any “farmscape plants” around greenhouses should be monitored and may need to be treated as trap plants. Trap plants are used to draw out pests away from greenhouse crops. To reduce the pest population on trap plants, natural enemies are released or selective pesticides are applied.

In some cases the natural enemies may not exist in high enough numbers when pest populations generally increase. Predator/prey population balances are influenced by the timing of available nectar, pollen and alternate prey/hosts for the natural enemies. Also, for most systems, it is not known if the natural enemies would actually move from the habitat plants onto the greenhouse crop and attack the pest.

Farmscaping, like other components of sustainable agriculture, requires more knowledge and management skill on the part of the grower than conventional pest management or even the current systems of using natural enemies.

Outdoor habitat plants

When considering habitat plants for the outdoor landscape, plants should be chosen that provide a good habitat for the desired predators and/or parasites, and at the same time, do not harbor insects that are likely to become pests, unless treated as trap plants. Growers should select plants that do not create new problems. For example, avoid invasive plants, those that may become weedy and those that may act as reservoirs for diseases that attack surrounding crops.

Habitat plants used to attract natural enemies in outdoor farmscapes have commonly been non-native annuals such as buckwheat, sweet alyssum, faba bean, dill, coriander and plants in the sunflower family. In many instances, floral structure is an important consideration. Beneficial insects with short mouthparts, such as tiny parasitic wasps, find it easy to obtain nectar and pollinate plants in the parsley and sunflower families because of the small, shallow flowers of these species. Plants that possess nectar sources outside the flower, such as faba beans, cowpeas, vetch and several native ground covers, provide beneficials with easy access to an important food source in addition to the nectar and pollen of their flowers.

It is not yet known whether natural enemies that are attracted to native plants translates into fewer pests in the greenhouse or in an outdoor production or retail yard.

Perennials as habitat plants

Native perennials have the advantage of remaining established for many years and increasing in floral area over time. A Michigan State University study looked at 43 native Michigan plants to learn whether native Midwestern perennials plants could provide similar benefits as non-native annual plants to support native natural enemies. The study also sought to determine if a succession of flowering species would be able to provide pollen and nectar resources over much of the growing season.

Plants were chosen based on their bloom periods and ability to survive agricultural habitats. The study showed 16 of the plants tested were highly attractive to natural enemies and pests.

For a complete list of plants that were classified as highly attractive, moderately attractive and with low or no attractiveness, see: http://nativeplants.msu.edu/menu.htm. The website offers a good overview of the project plus more detailed information about the individual plants.

Tina Smith is extension floriculture specialist, University of Massachusetts, (413) 545-5306; tsmith@umext.umass.edu

Thanks to University of Massachusetts entomologist Roy Van Driesche, for reviewing this article.

|

Tina Smith

Tina Smith