Quite a lot has changed in 24 months. Plastics for containers, irrigation and polymer coated fertilizer are more abundant. Fertilizer costs are stabilized (although likely at a new baseline that is higher than pre-COVID). Peat is being readily harvested and well-poised to manage customer demand. Droughts have been averted on the West Coast through record rainfalls and snowpack. As a result, on-demand and on-time supply of the needed natural and manufactured resources is on the rebound — minus the continued labor and trucking issues.

Lest we forget, disruptions to supply chain processes across the board have caused product availability to dwindle nationwide in past years and decades. Talk at major trade shows was focused on stockpiling supplies, and dare we say hoarding, with an eye to an uncertain future. We are all keenly aware of the issues surrounding plastics and containers, as well as the dramatic rise in fertilizer prices. However, nothing hit home to the industry like the scarcity of peat and rising cost of shipping bark and intensifying outcry that accompanied this growing problem.

We have been here before. While Canadian sphagnum peat suppliers are now having healthy harvests again, what happens in the future when peat harvests are limited by uncertainty of weather? Consider the other major U.S. substrate component, bark. Bark prices fluctuate based on standard supply and demand economic principles. As fuel costs rise, bark is used as a fuel source to supplement energy. As housing crises arise or new construction slumps, less lumber is cut and there is less bark available to age and ship. We had our taste of competition and shortages of bark both in the early 1990s and 2000s. While it has historically rebounded, this cyclic nature should be expected again — possibly much sooner than later based on some forecasts.

Also consider the rapidly rising substrate end-users. Globally, small fruit, hemp, medicinal marijuana and leafy greens operations are shifting to soilless production, increasing demand for substrate materials. In the U.S. alone, COVID also resulted in the creation of millions of new gardeners. As new soilless growers and gardeners join in the production of soilless culture, more and new substrate components will be required to satisfy their demand.

Another looming concern for the peat industry is the perceived negative environmentalism and sustainability — making headlines in the New York Times and National Geographic to name a few. These articles have resulted in public backlash towards the use of sphagnum peat — today’s gold standard for soilless substrates. This backlash against the peat industry has been growing at a rapid pace, to where we hear consumers and the public discussing peat in everyday conversations with only the “facts” found via social media and non-ag related news. More than ever, soilless production of ornamentals and food are in the spotlight. The horticultural industry, growers and allied suppliers alike, must inform the consumer we remain the “green” industry.

A comparison was presented by one of my mentors in recent discussions that bears weight in this op-ed. A decade ago, researchers found that while the use of neonicotinoid chemicals effortlessly control major pests like scale, it can be devastating to insect populations. There was major public outcry, and it was expected that we would have to end their use to save the bee populations. However, 10 years later, we never hear mention of this, and imidacloprid is used regularly and ubiquitously. Did the problem go away? No — imidacloprid — when properly used provides a valuable tool to combat insect pests without negative effects on the bee population.

There is less mention, or one may say disregard, of the habitat loss, pollution and climate change decreasing the number and diversity of insect populations. Think about it — when was the last time you had to clean bugs off your windshield after a road trip? My guess is not often and 10 or 15 years ago it was nearly standard practice. All this to say, finger pointing followed by quickly forgetting as we move on with the next news cycle is common and can have dire consequences for our industry. Perhaps the clamoring surrounding peat usage will be forgotten, but perhaps it is here to stay as it is in the United Kingdom, which has outlined a ban on all peat-based gardening products by 2030.

There has been much discussion of using “alternative” materials such as coir and wood fiber to address substrate shortages and increasing number of users. These are viable alternatives and becoming ubiquitous, but may require a learning curve when incorporating into production. Like bark, wood products are susceptible to being used as a low-cost fuel for energy. Significant resources are required to wash coconuts prior to use as a coir. Additionally, coir must be transported, typically via shipping containers, to North American growers with availability and pricing varying based on your U.S. location. There are also mentions of social justice surrounding coir production that may impact consumer perceptions in the future.

We still routinely hear the increasing need for affordable, regional materials to improve availability and reduce transportation costs. In the Gulf South, we have vast deposits of sugarcane bagasse in which research is underway to determine suitability and use in soilless substrates. Other regions have similar options that may yet have a major commercial entity backing the use of their byproducts, so it may take some specific investigation and time investments, but options are out there.

Another issue that is constantly discussed is the need for substrate consistency that leads to a uniform crop. Growers across the country continually complain about the lack of uniformity with their substrate from batch to batch. As the industry progresses into precision agriculture, the need for quality control is at an all-time high. Work with your substrate suppliers to ensure continuous quality control. I know they all strive for ultimate quality and want nothing more than your continued success.

What does this all mean for you? I hope your biggest take away is to always heed the past and know that while things are going well right now, it never hurts to plan for future uncertainties. Benjamin Franklin once said, “Failing to prepare is preparing to fail.” We strongly encourage all to be prepared. Be ready for the next turn of the dial, when prices skyrocket, or when availability rapidly diminishes due to unforeseen economic uncertainty or supply disruption from a pandemic. How can one do this? Perhaps not becoming overly reliant on any one material. It would be nice to be able to grow without water and fertilizer, but that is not a trick we have solved. In the meantime, experimenting and evaluating new techniques and materials on-farm so that you have experience and familiarity to quickly alter course. Explore new substrate materials. Perhaps you consider what it may take to implement substrate recycling into your production system. Substrate stratification is a new technique we are developing which allows multiple substrates to be layered or “stratified” in a container. Using this strategy, you can often get away with more “filler” material than you would by direct blending. Remember to think outside the box. One of our colleagues believes we will be producing our woody nursery shrubs hydroponically in the coming years, and why not? Bare root production is standard for many shrubs and trees, how could hydroponic production not be in play? The world is changing, and we must remain ever vigilant to ensure we adapt.

We close this op-ed with an eye to the maybe not-so-distant future in which substrates and soilless production systems become something entirely unfamiliar. Thus, we believe there are big changes ahead to address the ever-growing specialty crop industries that will be essential in feeding, sowing and clothing the world. Some folks doubt our ability to learn from the past, believing we continue using the same substrate systems, albeit with some minor upgrades. Some believe we may need to revisit filling containers, in part, with sterilized, mineral soils to increase water storage and delivery to address micro- and prolonged droughts. However, we believe the substrates of the future will be unrecognizable today. For example, we may use 3D technology to print containers with optimized shape for the crop or production system. Maybe it’s 3D printed organic media, mineral nutrient latent substrate that consists of micro-tubes, like xylem — nature’s solution to water and nutrient transport in vascular plants. We suggest you also conduct thought experiments regarding how best to reimagine and optimize an antiquated system with existing or novel technologies. Either way, we look forward to the substantial substrate innovations to come.

Get curated news on YOUR industry.

Enter your email to receive our newsletters.

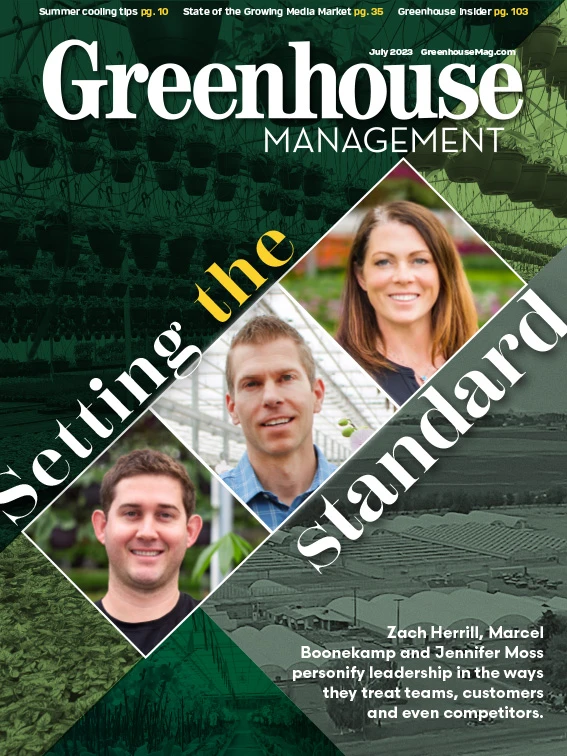

Explore the July 2023 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- pH Helpers

- Society of American Florists accepting entries for 2025 Marketer of the Year Contest

- Sustainabloom launches Wholesale Nickel Program to support floriculture sustainability

- American Horticultural Society welcomes five new board members

- Color Orchids acquires Floricultura Pacific, becoming largest orchid supplier in U.S.

- American Floral Endowment establishes Demaree Family Floriculture Advancement Fund

- The Growth Industry Episode 3: Across the Pond with Neville Stein

- 2025 State of Annuals: Petal power