According to the data from our 2021 State of Tomato Market research report, CEA tomato operations are keenly focused delivering the top-end flavor and crop quality that today’s produce consumers expect and demand.

Kentucky Fresh Harvest in Stanford, Kentucky is a new 11-acre greenhouse tomato grower, having just seeded its first commercial crop (last year was the group’s pilot crop) of indoor cherry and grape tomato varieties.

Trevor J. Terry, the farm’s marketing and communications lead, says he believes most growers in the segment are and should be focusing on flavor and final crop quality.

“Right now it is all about differentiation, and what differentiates Kentucky Fresh Harvest is our attention to quality and freshness,” he explains. “We’re out here to redefine local and a big part of that is proximity to our customer base - but the quality is all thanks to our team of top notch growers.”

The third metric that growers said they are increasingly seeking out from their greenhouse tomato genetics — disease resistance — is another crucial piece of the production puzzle down at KFH.

“...what we need is to lean into innovation and focus on building equity among all stakeholders in the chain. It can’t just be growers telling the distributors ‘this is what works for us’ and vice-versa. We’ve got to take a collaborative approach.” -Trevor Terry

“Growing in Kentucky comes with some very specific risks when you consider our past as an intense tobacco production region, and now we have this Tomato Brown Rugose Virus to contend with which is a huge consideration for the entire supply chain,” Terry says.

One segment of the industry that Terry would like to see some improvements take place is on the logistics side.

“What we have currently is a wasteful and unsustainable system,” he explains. “What we need is to lean into innovation in ag and focus on building equity among all stakeholders in the food chain. It can’t just be growers telling the distributors ‘this is what works for us, so do it’ and vice-versa. We’ve got to take a collaborative approach to feeding people that begins and ends with farmworkers and customers.””

Extension Q&A

Benjamin Phillips is the vegetable crop expert at Michigan State Universities’ Saginaw Valley Research and Extension Center in Central Michigan. Although he mostly works with field-growers, Phillips does have some interaction with the local greenhouse produce operations in the area.

We asked Phillips his thoughts on a few of the data points that came out of our grower-facing research efforts this year. Below are his insights and reactions to some of the data:

Data point No. 1: growers ranked the following variety attributes as “most important”: #1 Flavor, #2 Yield, and #3 disease resistance.

Phillips: These three factors are interconnected. A component of yield is the percentage of tomatoes that leave the production area and successfully reach their customers. And one way yield has been conserved in a globalized economy is by breeding for physically tougher tomatoes to handle the rigors of transportation. The mouthfeel of these tough tomatoes can affect how customers perceive flavor. They may taste the same but if they are not juicy and soft, it doesn’t feel right. Similarly, disease resistance is related to yield. Summer-season crops seem to get more flavor than winter greenhouse tomatoes. I don’t know all the reasons. But, it’s probably one of those things nature does best and is tough to replicate indoors through a harsh season. Essentially any variety grown in summer will taste better.

My advice? Focus on flavor and disease resistance, produce in the summer, learn the tricks and ins-and-outs of each variety, and harvest with care at the timing that is best for transporting them and preventing cracks. Yield will come along with your care. In my area of Michigan the popular summer-produced tomato varieties are Red Deuce, Primo Red, Florida 47, several of the Mountain varieties, Frederick, Sweet 100and Sun Gold.

_fmt.png)

Data point No.2 : Growers indicated they mostly grew tomatoes indoors in soil-based growing media systems (65%), hydroponic systems (26%), and Aquaponics (1%) with 7% answering “Other.”

Phillips: In my area of Michigan, the fresh market growers here are 99% in-soil producers, with a smaller percentage of that using a sort of hybrid hydroponic system with bags or buckets, or pots with potting mix arranged in rows with drip emitters like the type that are used in hanging basket flower production. I do not see these growers ever fully adopting hydroponic systems because of the lost opportunity for other uses of the space. With that type of system, the natural inclination would be to produce all winter to recoup the cost, and with that comes the additional cost of heating. Instead, when soil-pathogens get to be limiting, they have switched to bag-culture or grafting with excellent results. Of those two options, grafting comes with a higher learning curve and price tag.

In my experience, aquaponics is a doomed venture for most growers. Here in Michigan (and probably other places), you cannot process fish into filets without an inspected facility, but most shoppers do not want to buy whole fish. It is an entirely separate marketing project. Further, the needs of plants and fish changes as they grow or change populations. You can almost never treat them both appropriately when they are linked in a closed loop system. You produce one at the sacrifice of the other, whether it’s fresh water, nutrients or pest control. The only way I think a producer could make it work is by plumbing separate inlets and outlets for each population: plants and fish. That way you can utilize some of the potential benefits, but also disengage the closed loop on the fly for special treatment of each population. But, I have never seen a system like this because it is twice the plumbing and cost. So I see fish and plants suffering alternately, or simultaneously. You could quote Ron Swanson, from Parks & Recreation here: “Whole-ass one thing.”

Data point NO. 3: Growers are seeing 1-3% (25%), 4-10% (34%), and greater than 10% (41%) pricing premiums based on finished crop quality.

Phillips: You have to learn ideal harvest timing on each variety and pick them when they need picking. Or, you could choose to grow only the varieties that align with what you are willing to go through to keep top quality.

Heirloom tomatoes are quite popular, and these have old traits that do not protect them from skin cracking and splitting. So, they absolutely must be harvested before they are at peak ripeness to reduce the risk of these cracks and fruit bruising during harvest and transportation. Newer hybrids are more resistant to these things, and can be picked closer to peak ripeness, but can also benefit from early picking to maintain good quality. Last year, I saw a lot of tomatoes produced here in Michigan that were picked at or after peak ripeness, and by the time they were put on display at a farm stand retailer, they were puckered and wrinkly from moisture loss.

Essentially, you pick with the same timing as you would for peak ripe, but you move it up a few days and harvest the pinks, blushers, or breakers. Keep the tomatoes in a non-refrigerated, shaded, and ventilated space like a barn, shop, or garage. Remove any split or squished, or leaking tomatoes from the lot before putting them up to avoid fruit fly and sap beetle pests, and put those culls far away from your storage or sale area. If those pests start up, give that area a clean break from holding tomatoes and sanitize it thoroughly.

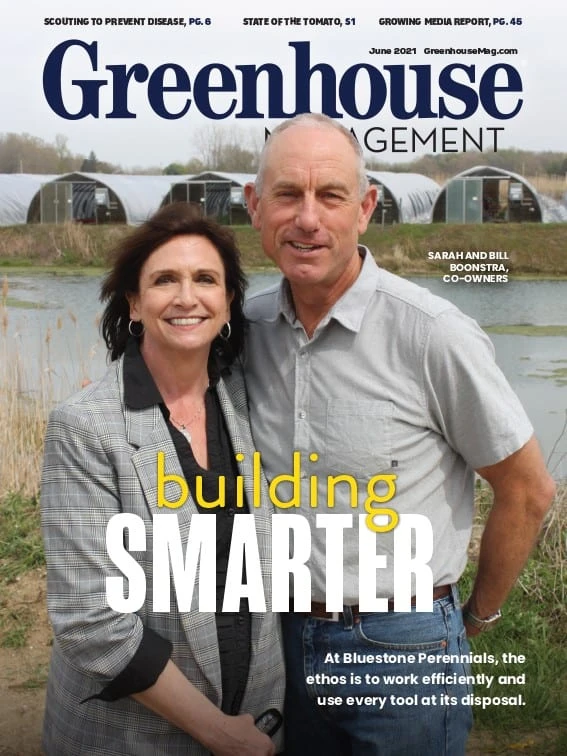

Explore the June 2021 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Greenhouse Management

- Anthura acquires Bromelia assets from Corn. Bak in Netherlands

- Top 10 stories for National Poinsettia Day

- Langendoen Mechanical hosts open house to showcase new greenhouse build

- Conor Foy joins EHR's national sales team

- Pantone announces its 2026 Color of the Year

- Syngenta granted federal registration for Trefinti nematicide/fungicide in ornamental market

- A legacy of influence

- HILA 2025 video highlights: John Gaydos of Proven Winners